Dear Rich: My daughter, who has Down syndrome, loves to color design coloring books such as Ruth Heller's Designs for Coloring. She has a good eye for color and puts hours into each picture. She would like to submit her work to a book compiled by Woodbine Publishers about Down syndrome artists. Is she allowed to? We think you should try to get permission first. Assuming you can get in touch with the copyright owners, we believe they are likely to grant permission. We think that because the reproduction won't harm their sales, it's the right thing to do, and it's good public relations. If you can't get permission, we think you can probably get away reproducing the imagery without permission (though we can't guarantee that result).

How do you get permission? The copyright is likely held by the Ruth Heller Trust Fund but we think the place to start your request is with Grosset and Dunlap/Penguin Putnam Books for Young Readers, the publisher. They have an online permission system and a set of FAQs explaining the process and their online database indicates they control about a dozen Ruth Heller books. If the coloring book you are using is not covered, perhaps G&P can lead you to the proper source or to the trust.

Can you use it without permission? We think including one or two images (with proper attribution) would probably not trigger a cease and desist letter. Although the copyright pages of the coloring books don't specifically grant permission for uses like yours, a coloring book is an implied invitation to create a derivative work. It can also probably be argued that the sale of a coloring book implies a limited right to post and reproduce the resulting "colored-in" works. And for what it's worth, the company has not objected to the posting of colored-in versions of their imagery at Amazon. Again, we can't guarantee that the copyright owner won't object to your use, but it's difficult to imagine that they would.

Showing posts with label permission. Show all posts

Showing posts with label permission. Show all posts

Making Merchandise from Video Game Characters

Dear Rich: For a while I have been making digital merchandise based off of famous movie and video game characters. At first I wasn't really making any money off of them. I know now that not making a profit doesn't change anything as far as trademark violations, but I thought it did before, so I stopped selling the merchandise a while ago because I had started making real money and didn't want to make money off of other people's creations without their permission. But now, after so many months, I find myself still wanting to make and sell that merchandise, and other people are asking me to as well. Its a bit frustrating, because I see other people creating things based off of trademarked characters, both in my market and in other markets on the internet. Like all of the Star Trek merchandise you see on Etsy. What's the likelihood of a small one-person business like me getting permission to create merchandise like this? If it's possible, how do I do it? The likelihood of getting permission is very slim. Owners of video game characters usually only deal with established merchandisers (with serious sales voodoo). Also, they often enter into exclusive licenses. That means they can't grant permission to you without violating their license with someone else. It's possible that if you were offering a new product category, you might have a chance. But that's tough to pull off. (PS. Here's the lowdown on trademark licensing.)

How do other people get away with it? It's a matter of odds. The owners of valuable character properties usually put their resources into pursuing the bigger fish, and for the most part, that often bypasses individual sales at Etsy or eBay. So, unless the trademark owner is intending to make an example of a small fry infringer, a cease and desist letter may be sent, and that's sometimes the end of it.

What should you do? We wish it wasn't frustrating to get permission. Like, wouldn't it be great if you could pay "per impression" for reproductions of licensed characters. Of course, that may blow any standards of quality ... but hey, merchandise happens. Anyway, infringement is always a gamble and we'll leave the risk assessment to you.

How do other people get away with it? It's a matter of odds. The owners of valuable character properties usually put their resources into pursuing the bigger fish, and for the most part, that often bypasses individual sales at Etsy or eBay. So, unless the trademark owner is intending to make an example of a small fry infringer, a cease and desist letter may be sent, and that's sometimes the end of it.

What should you do? We wish it wasn't frustrating to get permission. Like, wouldn't it be great if you could pay "per impression" for reproductions of licensed characters. Of course, that may blow any standards of quality ... but hey, merchandise happens. Anyway, infringement is always a gamble and we'll leave the risk assessment to you.

Will Negative Review of Art Reduce Permission Chances?

Dear Rich: I'm writing an academic essay on art criticism and some artworks I criticize and others I say better things about. In looking for free copies of these images, how do I handle the galleries whose artists are coming under critique? Is it ethical to hide the fact that they won't come out so well? I feel far more comfortable asking for free copies of images from galleries and museums in which the artist comes out better. We know what you mean about that ethical thing. The Dear Rich Staff has worked as a reviewer and sometimes we feel funny panning somebody's work even if we didn't have to ask permission for anything. That's because we know how much effort went into the thing and we feel bad deflating the tires, so to speak. On the other hand, everybody's a reviewer these days so maybe reviews really don't matter any more.

Right, you had a question. Obviously your chances of obtaining permission are reduced if you inform the person from whom you're seeking permission that you intend to pan the artwork. So, our suggestion would be not to mention it. Like Admiral Hopper used to say, "It's easier to ask for forgiveness than it is to get permission." Though some may disagree with that approach, we feel it's fine in this situation. After all, academic criticism is valuable and is intended to provide benefits to the artist and the public. So, we see nothing wrong with simply stating that you are preparing an academic essay and need a high quality reproduction of the work for reproduction with your essay. If you cannot get permission and you are going to produce a printed publication, you may be able to reproduce thumbnails under fair use principles -- at least that's been the trend recently for books and websites. And of course, though it may be expensive, some artwork can be licensed with few questions asked through sources such as VAGA and ARSNY. (Columbia University has a site explaining the licensing principles of museums and galleries.) And while you're at it, we're curious what you think of this artwork?

Right, you had a question. Obviously your chances of obtaining permission are reduced if you inform the person from whom you're seeking permission that you intend to pan the artwork. So, our suggestion would be not to mention it. Like Admiral Hopper used to say, "It's easier to ask for forgiveness than it is to get permission." Though some may disagree with that approach, we feel it's fine in this situation. After all, academic criticism is valuable and is intended to provide benefits to the artist and the public. So, we see nothing wrong with simply stating that you are preparing an academic essay and need a high quality reproduction of the work for reproduction with your essay. If you cannot get permission and you are going to produce a printed publication, you may be able to reproduce thumbnails under fair use principles -- at least that's been the trend recently for books and websites. And of course, though it may be expensive, some artwork can be licensed with few questions asked through sources such as VAGA and ARSNY. (Columbia University has a site explaining the licensing principles of museums and galleries.) And while you're at it, we're curious what you think of this artwork?

Can We Pilfer Celebrity Photos From IMDB?

|

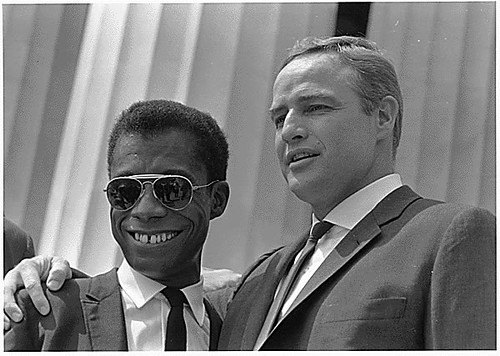

| Marlon Brando and James Baldwin at 1963 March on Washington |

Operating without clearance. If you work for a website company, you're best off not jeopardizing your job by using unauthorized photos. The price you'll have to pay -- time, threats, lawsuits and payments -- if you're caught will far outweigh the licensing costs. If you're just posting a photo occasionally to your personal blog, you're less likely to get hassled but beware that photo agencies employ various means of tracking digital photo use including digital watermarks and embedded metadata.

Right of publicity. The rules we provide here are for websites where you are using the celebrity photo as a means of illustrating a story about the celebrity -- for example, you're discussing the funny side of Mike Tyson. If you are using the celebrity photo to imply endorsement of your site or to sell a product or service, you'll need the celebrity's permission as well.

Public domain photos. There are some public domain photos of celebrities. Try sites such as Wikimedia and read and observe the terms of the licenses. We're not so sure about so-called public domain photos at other sites -- that is, whether the photos are actually in the public domain. We typed in "public domain celebrity photos" and found mixed results (including pictures of Dwight Eisenhower and Britney Spears -- we don't want to think about the potential mash-up!). Of course photos taken by government employees -- for example, Elvis shaking hands with President Nixon (soon to be a movie) are in the PD. We think that's the case with our photo of Marlon Brando and James Baldwin (above) -- perhaps taken by an FBI agent. (And here's a related video made around the same time).

Those 70's Lyrics: Do I Need Permission?

Right, you had a question. To some extent, it may depend on what you're doing with the lyrics. If you're using them for purposes of criticism and commentary and are only reprinting a chorus or verse -- usually four or five lines -- you can probably rely on fair use as a defense. (But, as we always warn, there's no guarantee that a music publisher won't hassle you over fair use claims). If you're reprinting more than that, or you are not commenting upon the lyrics, you should seek permission from the music publisher to reprint a song’s lyrics in a book. The fees for such uses are not fixed, so a music publisher can charge whatever the market will bear and fees range from $50 to hundreds of dollars to reprint lyrics in a book. We've provided a "lyric permission" letter in our permissions book, but nowadays you can probably work it out with an email exchange. You can research music publisher information at ASCAP, BMI, or Harry Fox. Alternatively (as the lawyers like to say), if you are self-publishing to a limited audience, you can take the risk and operate without permission, though successful writers opine against that.

Eat Pray Ask Permission?

Dear Rich: I'm interested in knowing if you have ever encountered clearing an "inspired by" situation. For example, I have written a piano solo inspired by the novel, "Eat Pray Love." I have not put that information on the cover of the piece because myinstinct tells me "Eat Pray Love" would need to be cleared. The Dear Rich Staff kind of missed the boat on Eat Pray Love. It's not that we don't like Chicklit or RomComs or Julia Roberts (We felt bad for her when she broke up with Kiefer Sutherland ... and then felt happy for her when she started dating Jason Patric because he was so great in that Kathryn Bigelow vampire movie). Anyway, we're glad you found the movie (or book) inspiring enough to write a piano solo. (This movie might inspire us to write a song, however.)

Right, you had a question. From a purely legal POV, there's nothing preventing you from calling your composition Eat Pray Love or from stating that it was inspired by Eat Pray Love. Many artists have named compositions after books and films (and vice versa). But you will run into problems if you imply that the owners or creators of the book or movie somehow endorse what you're doing. That might be the case if you have included an image of the book cover or a picture of Julia with your sheet music or performance. You also may run into problems if buyers are confused with the song that's become associated with the movie.

Wants to Use Magazine Imagery in Book

Dear Rich: I am writing a book about an art technique using a national magazine. I can illustrate the process using the magazine without actually showing any of it's actual images, (see picture) but I must use the name as it is the only magazine that will work with this process. I have contacted the company and so far no one has been able to help me. The other product that I use has given me permission and is going so far as to help me promote the book because it will help them. This would also be the case with the magazine. I will be adding value rather than compromising it. I will list them in my sources. Would this be considered fair use? Do I need to have their permission to use their name? This reminds us of when our cousin Andrew used to paste rubber cement on a piece of wood and then apply rubber cement to a magazine picture and press them together after they dried (and I think he ran water over it until the paper washed off). He ended up with a piece of wood with an image on it, except you could see the wood grain, too. Kind of an old-timey look. He priced them at $50 or $100. We were about 13 at the time and that seemed a lot to charge for something you made with rubber cement. He told me, "If you don't charge a lot, people won't take it seriously." He was so young to know that.

Right, you had a question. We think you will be fine using the name of your magazine within your book. That's a trademark issue not a copyright issue and editorial uses of trademarks -- for example, talking about a magazine in a how-to book -- does not require permission. A conservative approach would also be to add a disclaimer at the front of the book to the effect that you and your publisher have no association with the magazine and that all rights in the magazine vest in the magazine owner. If you use imagery from the magazine, you'll trigger copyright issues and probably need permission either from the magazine or, if the magazine doesn't own the rights, from the photographer or designer who created the materials you're using. We think selective uses of the magazine in the context of a crafts project would likely be excused as a fair use since it is clearly a transformative use, but as Dear Rich readers know, fair use is just another word for a lawsuit, because that's often the only way you can prove fair use rights. As for the fact that your book adds value to the magazine, that may or may not be true, but it probably won't have much effect on your claim of fair use.

Right, you had a question. We think you will be fine using the name of your magazine within your book. That's a trademark issue not a copyright issue and editorial uses of trademarks -- for example, talking about a magazine in a how-to book -- does not require permission. A conservative approach would also be to add a disclaimer at the front of the book to the effect that you and your publisher have no association with the magazine and that all rights in the magazine vest in the magazine owner. If you use imagery from the magazine, you'll trigger copyright issues and probably need permission either from the magazine or, if the magazine doesn't own the rights, from the photographer or designer who created the materials you're using. We think selective uses of the magazine in the context of a crafts project would likely be excused as a fair use since it is clearly a transformative use, but as Dear Rich readers know, fair use is just another word for a lawsuit, because that's often the only way you can prove fair use rights. As for the fact that your book adds value to the magazine, that may or may not be true, but it probably won't have much effect on your claim of fair use.

Do I Need Permission to Publish My Animation?

Dear Rich: I have worked in animation for 30 years (as an animator, visual development artist and storyboard artist) and I decided to put together a compilation book of my own artwork (from games, TV shows, and animated Feature films) to sell. It would be self published, probably in a print run of 500 copies, and I would primarily sell it directly at comic book shows and my own website (and perhaps at some specialty shops). I am wrestling with whether to go ahead and print it, without seeking permissions. But, after much deliberation, I began the request process with a few clients that I have recently been working with and so far so good; I have been getting permission with only one firm "NO" so far. But there’s another issue. I used to work at an animation studio that did everything from commercials to TV shows, games, and even effects for feature films. I did TONS of design work for them, on properties they were trying to develop themselves and for clients coming to them for development. The tricky part is that this particular studio has been out of business since 1996 and so I have no way of knowing who actually owns the rights to some of the artwork. So, here are my questions: (1) Do I need to get permissions at all? (2) What is the worst case scenario for not getting permission? (3) Is it legal to just say that I tried to locate the rights holder and could not? And (4) What happens to the intellectual properties of a company that has been out of business for 15 years? Can we answer your questions in reverse order? For some reason we find that more fun. (And speaking of permission, thanks for letting us use one of your images.)

(4) What happens to the intellectual properties of a company that has been out of business for 15 years? The successor to the business owns it. If there is no successor it becomes an orphaned work and a minor annoyance for those who must get permission. For example, if an author has assured her publisher that she will get permissions for her book, she'll have a problem with an orphaned work, and the publisher may make her take the work out. We don't think you need to worry much about that issue, as we explain below.

(3) Is it legal to just say that I tried to locate the rights holder and could not? It's still infringement but it's not a bad idea to put a statement like that on the copyright page and to disclaim copyright in those works. That doesn't mean you may not have to eventually pay for their use but if you can document your attempts to find the owner, that will go a long way to mediating any damages you might be assessed (in the way outside chance you end up in court).

(2) What is the worst case scenario for not getting permission? The worst case is that you run into one of these types and you can't seem to remove their teeth from your pants leg. They will drag you into court and not let go until you get out your checkbook. In your case, this worst case is not a very likely outcome. You have several factors buffeting your position.

First, you have an excellent fair use argument, similar to the argument raised in this case involving the artist Basil Gogos. Gogos created covers for monster movie magazines and the copyright owner of the monster movie magazines sued over the use of the covers in a Gogos biography. A court determined that the use was transformative and permitted it as a fair use. One of the factors in the artist's favor was that the magazines were no longer in print. Another was that the artwork was part of a biography/retrospective of the artist. Another reason that you may not have to worry is the limited publication. It would be difficult for a copyright owner to claim much in the way of damages if only 500 copies were distributed (and money is the main motivator for lawsuits).

1) Do I need to get permissions at all? See above. By the way, did you know it's easy, fast and kind of fun to search copyright office records? We're working on a video to explain the process but until then, check out the Copyright Office search engine.

(4) What happens to the intellectual properties of a company that has been out of business for 15 years? The successor to the business owns it. If there is no successor it becomes an orphaned work and a minor annoyance for those who must get permission. For example, if an author has assured her publisher that she will get permissions for her book, she'll have a problem with an orphaned work, and the publisher may make her take the work out. We don't think you need to worry much about that issue, as we explain below.

(3) Is it legal to just say that I tried to locate the rights holder and could not? It's still infringement but it's not a bad idea to put a statement like that on the copyright page and to disclaim copyright in those works. That doesn't mean you may not have to eventually pay for their use but if you can document your attempts to find the owner, that will go a long way to mediating any damages you might be assessed (in the way outside chance you end up in court).

(2) What is the worst case scenario for not getting permission? The worst case is that you run into one of these types and you can't seem to remove their teeth from your pants leg. They will drag you into court and not let go until you get out your checkbook. In your case, this worst case is not a very likely outcome. You have several factors buffeting your position.

First, you have an excellent fair use argument, similar to the argument raised in this case involving the artist Basil Gogos. Gogos created covers for monster movie magazines and the copyright owner of the monster movie magazines sued over the use of the covers in a Gogos biography. A court determined that the use was transformative and permitted it as a fair use. One of the factors in the artist's favor was that the magazines were no longer in print. Another was that the artwork was part of a biography/retrospective of the artist. Another reason that you may not have to worry is the limited publication. It would be difficult for a copyright owner to claim much in the way of damages if only 500 copies were distributed (and money is the main motivator for lawsuits).

1) Do I need to get permissions at all? See above. By the way, did you know it's easy, fast and kind of fun to search copyright office records? We're working on a video to explain the process but until then, check out the Copyright Office search engine.

He Needs Poets' Permission for Choral Work

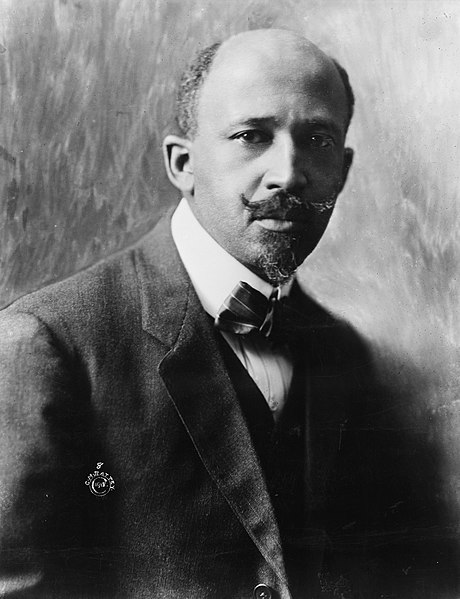

Dear Rich: I am a professional composer and I am looking to gain the text permissions from several authors for use in a commissioned choral composition I am writing. The author's works are found in a book entitled Earth Prayers, published by HarperCollins Publishers. The work I am writing has been commissioned by The Bucks County Choral Society. The authors are as follows; Wendell Berry, W. E. B. DuBois, Joyce Fossen, and Stephanie Kaza. I am comfortable with the fact that I may not be able to get any permissions from these authors. The DuBois permission I am sure would be through some estate. Since Berry is still alive and his poetry is widely published, he may deny permission as well. He may not even like music, though I cant imagine that. I just would like the chance to ask him. Joyce and Stephanie, I am not sure of. My initial research of their works online have yielded little results. The Dear Rich Staff wishes you well and hopes you don't run into the kind of problems faced by composer Eric Whiteacre (but if you do, there's always crowdsourcing). As for your permissions:

- It's possible that some (if not all) works by W.E. DuBois (above) are in the public domain. DuBois lived from 1868 to 1963. Any works of his published before 1923 -- for example Darkwater: voices from within the veil (published in 1920) -- are in the public domain. And all works published before 1964 were subject to renewal; most works were not renewed. Many of DuBois' works written after 1923 have been the subject of multiple copyright claimants, a strong sign that these works are either in the public domain, or that nobody is pursuing rights. You can check these details further by searching Copyright Office records.

- Stephanie Kaza appears to retain copyright in her work, at least according to Copyright Office records. So, you could start your search for her by checking with her most recent publisher Shambhala. They published her recent (2005) work, Hooked! Buddhist writings on greed, desire and the urge to consume.

- We love Wendell Berry (especially his recent book, Remembering).You should probably start your search through his current publisher, Counterpoint, which maintains the Wendell Berry website.

- We located Joyce Fossen in the Copyright Office records and if it is the poet you're seeking, she appears to have passed away in 1989. The copyright claimant for her work is a George J. Fossen and we imagine he would be the person to contact for permission (although we have no way of locating that information).

Why Can't I Take Photos in Court Room?

Photo Week #2

Dear Rich: I want to photograph an empty courtroom but the people at the courthouse told me photographers weren't allowed unless a judge approved it. I just want to photograph the court room, not the people. It's possible that the courthouse personnel mistook your request. They may have thought you wanted permission to photograph during a business day or trial. That's a matter usually left up to the judge. Otherwise, the regulation of photography within government buildings is determined by the relevant city, county or state government (as discussed yesterday). Alas, taking photos of public buildings is sadly over-regulated in a post-9/11 world. You need to find the local public official who can grant permission -- often indicated somewhere within the local rule or permit requirement.

Today's public domain photo: by Ann Rosenera, is a 1943 image of California shipyard workers on the ferry to the Richmond Shipbuilding Company yards.

Dear Rich: I want to photograph an empty courtroom but the people at the courthouse told me photographers weren't allowed unless a judge approved it. I just want to photograph the court room, not the people. It's possible that the courthouse personnel mistook your request. They may have thought you wanted permission to photograph during a business day or trial. That's a matter usually left up to the judge. Otherwise, the regulation of photography within government buildings is determined by the relevant city, county or state government (as discussed yesterday). Alas, taking photos of public buildings is sadly over-regulated in a post-9/11 world. You need to find the local public official who can grant permission -- often indicated somewhere within the local rule or permit requirement.

Today's public domain photo: by Ann Rosenera, is a 1943 image of California shipyard workers on the ferry to the Richmond Shipbuilding Company yards.

Photo Permits and Public Property

Photo Week #1

It's our annual Photo Week Celebration in which we answer questions regarding photography.

Dear Rich: I am an amateur photographer and have taken photographs of many public places within the city in which I live (e.g. parks, beaches, statues and other public works, buildings, streets). I compiled these photographs for an advertising campaign that I wanted to start of which the photographs would be used for commercial purposes. Now I find that a city issued permit is needed to commercially photograph, anywhere in the city. According to one city website, photographs cannot even be compiled, as part of a commercial portfolio without first getting a permit from the city, even if these photographs are not being sold. My questions is this: My registration for copyright at the copyright office is now in progress (although temporarily delayed at my request). Can I be penalized or fined by the city if my photographs are registered and made public (published) by the copyright office? Also, can I be sued for infringement if some of the photographs that I had taken and sent into the copyright office were of statues and other publicly displayed art works and buildings (which I now realize, may have been copyrighted by the artists). Start with the principle that a "permit law" created by a local government will have no effect on your ability to copyright your photos. Any permit law that attempts to limit your right to claim copyright would be preempted by federal law. In other words, even if the law says stuff about copyright, it would be invalid if challenged in court.

What's up with permit laws? Many cities and counties have permit laws for commercial photography and they're all pretty similar -- here's what Miami's law looks like. These laws require permits when shooting commercial photography in order to limit the impact of photo shoots on the public and to require insurance in case someone is injured during the shoot. As this article points out, the definition of commercial photography in these regulations is usually vague, so that a photographer who is not acting commercial -- working with models, props, crews, vehicles, or closing down traffic -- can usually manage without a permit.

Will the city chase you after the fact? It seems unlikely that a municipality will chase a photographer after the fact -- more likely if an incident occurred during the shoot. As for statues and public art, that's a different matter and we've discussed this issue previously (check out one recent example). That type of dispute involves the copyright owner and the photographer (not the municipality).

Today's public domain photo: from the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture photo website, a 60-minute-old agar plate culture from an air sample taken in a caged layer room of birds infected with Salmonella enteritidis.

It's our annual Photo Week Celebration in which we answer questions regarding photography.

Dear Rich: I am an amateur photographer and have taken photographs of many public places within the city in which I live (e.g. parks, beaches, statues and other public works, buildings, streets). I compiled these photographs for an advertising campaign that I wanted to start of which the photographs would be used for commercial purposes. Now I find that a city issued permit is needed to commercially photograph, anywhere in the city. According to one city website, photographs cannot even be compiled, as part of a commercial portfolio without first getting a permit from the city, even if these photographs are not being sold. My questions is this: My registration for copyright at the copyright office is now in progress (although temporarily delayed at my request). Can I be penalized or fined by the city if my photographs are registered and made public (published) by the copyright office? Also, can I be sued for infringement if some of the photographs that I had taken and sent into the copyright office were of statues and other publicly displayed art works and buildings (which I now realize, may have been copyrighted by the artists). Start with the principle that a "permit law" created by a local government will have no effect on your ability to copyright your photos. Any permit law that attempts to limit your right to claim copyright would be preempted by federal law. In other words, even if the law says stuff about copyright, it would be invalid if challenged in court.

What's up with permit laws? Many cities and counties have permit laws for commercial photography and they're all pretty similar -- here's what Miami's law looks like. These laws require permits when shooting commercial photography in order to limit the impact of photo shoots on the public and to require insurance in case someone is injured during the shoot. As this article points out, the definition of commercial photography in these regulations is usually vague, so that a photographer who is not acting commercial -- working with models, props, crews, vehicles, or closing down traffic -- can usually manage without a permit.

Will the city chase you after the fact? It seems unlikely that a municipality will chase a photographer after the fact -- more likely if an incident occurred during the shoot. As for statues and public art, that's a different matter and we've discussed this issue previously (check out one recent example). That type of dispute involves the copyright owner and the photographer (not the municipality).

Today's public domain photo: from the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture photo website, a 60-minute-old agar plate culture from an air sample taken in a caged layer room of birds infected with Salmonella enteritidis.

Disney Princess Permission

Dear Rich: I would like to begin offering tea parties and other party services where a particular princess hosts the event. I have seen a lot of party places advertising parties with specific Disney princesses. I am wondering do you have to get permission from Disney to say your having a tea party with say Cinderella or one of the princesses, and if so, how do I begin that process? We've located one source for permission though we can't guarantee it's still accurate. Try writing to The Walt Disney Company, ATTN: Margaret Adamic, Permissions, 500 S. Buena Vista Street, Burbank, CA 91521-6305. The phone number is (818) 569-3128. By the way, we've also written about using Disney princesses in indy movies and about using the princesses on stationery.

Can I use fashion trademark in movie?

Dear Rich: Please if you could let me know about using the Barney's name (Barney's New York) in feature film and presenting some space as its office. The lead actress gets an offer to work for Barney's from one of the managers, plot goes into different direction, and from her actions we conclude that she doesn't consider Barney's offer any more. So if it's part of the plot at all, it doesn't have a strong point. I would appreciate if you could respond to my dilemma. Short Answer Dept. You're probably fine with your planned use (although you should ditch the apostrophe as it implies you are dealing with purple dinosaurs not the store's apostrophe-free trademark). As we've said before, filmmakers and screenwriters have a First Amendment right to talk about and reproduce trademarks in films. However, such uses may trigger a lawsuit if a displeased trademark owner believes that your film is confusing consumers--that is, filmgoers mistakenly believe that Barneys New York endorses or is in some way associated with your film.

Creating the fake Barneys office. We believe your re-creation of the Barneys office is permitted under First Amendment grounds but that doesn't mean that you won't get hassled. As you know from reading our blog, there's a difference between being legally correct, and surviving the lawsuit that proves you're legally correct. Re-creating the office may trigger a wider range of objections -- for example, if you accidentally use a character with a similar name as a real Barneys employee in an unflattering manner, or if the film defames management or by implying that working conditions at Barneys violate the law in some way. An apprehension of a trademark's owner wrath can even kill a big-time Hollywood production. As our previous post pointed out, another problem in situations like this is that if your film becomes a success, your distributors and festival producers may demand releases for these uses. Hopefully, if you're successful enough to obtain distribution, you'll also be able to afford the legal power necessary to acquire the necessary rights.

Creating the fake Barneys office. We believe your re-creation of the Barneys office is permitted under First Amendment grounds but that doesn't mean that you won't get hassled. As you know from reading our blog, there's a difference between being legally correct, and surviving the lawsuit that proves you're legally correct. Re-creating the office may trigger a wider range of objections -- for example, if you accidentally use a character with a similar name as a real Barneys employee in an unflattering manner, or if the film defames management or by implying that working conditions at Barneys violate the law in some way. An apprehension of a trademark's owner wrath can even kill a big-time Hollywood production. As our previous post pointed out, another problem in situations like this is that if your film becomes a success, your distributors and festival producers may demand releases for these uses. Hopefully, if you're successful enough to obtain distribution, you'll also be able to afford the legal power necessary to acquire the necessary rights.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)