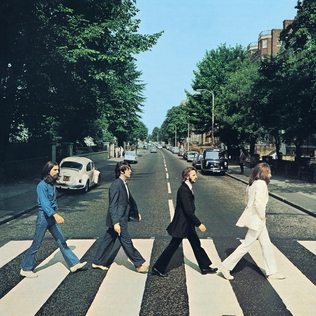

Dear Rich: On music CDs and in the movies I see images of different kinds of cars, and I wonder if the artist has had to pay any royalty to the car manufacturer. For example, the Beatle's Abbey Road album has a white Volkswagen Beetle right behind George Harrison. Does this imply endorsement of Beatle's music by Volkswagen Motor Company? And remember Walt Disney's use of a Volkswagen in the movie, The Love Bug. There are many classic old Fords and Chevys seen in movies all the time. Also, there is a musical group called REO Speedwagon. Using a car's image or trademark may (or may not) trigger problems on a CD cover or in a movie ... it depends on a few factors.

The Abbey Road Cover. The image of a VW on the Abbey Road cover (above) is unlikely to trigger any trademark issues because the usage is primarily editorial -- that is, it's an incidental use and no particular attention is drawn to the car. Of course, at the time, fans saw hidden meanings in the presence of the car (Beetle = Beatle) but it turns out the car was simply a vehicle owned by someone in a nearby flat. (BTW, the license of the car was stolen soon after the album came out). If consumers were likely to be confused into thinking that Volkswagen (or any other car manufacturer whose vehicle appears on the street) endorsed the Beatles (or vice versa), the car company never saw fit to take action. After all, if the world's most popular band at the time is including your product on a popular album, that's not something you're likely to complain about. (In general, it was a less litigious world back in 1970.) BTW, an editorial use of a trademark -- for example, a picture of a Ford truck in a documentary about trucks -- is not infringing.

Herbie and VW Marks. As for Herbie and the Love Bug movies, Disney removed the name and logos (scroll down) from Herbie in the first movie in the series. Apparently the company was concerned about claims of trademark infringement. But several years later when the sequel appeared (Herbie Rides Again) in 1974, VW sales were down and the VW company insisted that Disney put the trademarks and names back. (The names and marks stayed on Herbie for the subsequent four Love Bug sequels.)

REO Speedwagon. The band, REO Speedwagon, was able to get away with using the name and logo of the REO Speed Wagon company probably because the auto company had likely abandoned any claims to the mark when it ceased production in 1936 (or some time in the later 1940s -- we're not sure) or perhaps when the later owners of the REO Motor Company declared bankruptcy in the early 1970s. An abandoned mark is free for anyone to use, although ceasing production of an automobile is not always a clear sign as to the status of the mark.

As a general rule, you want to avoid making people think the car company is affiliated or endorses your product or service -- for example, calling your band Miata -- or diluting a famous mark by tarnishing its reputation in a commercial context. However, we also note that there's plenty of leeway in these standards as the Caterpillar company found out when they tried unsuccessfully to prevent the use of their villainous tractors in a George of the Jungle movie.

Showing posts with label artwork. Show all posts

Showing posts with label artwork. Show all posts

Can Rangoli Be Protected By Copyright?

Dear Rich: I am working on a children's book that explains how to do a type of folk art known as Rangoli. Rangoli is very popular and is made by millions of people all throughout India. The nature of this type of art, which has been practiced for many years, is that there are extreme similarities in the designs that people create, and designs are also passed on so that they are perpetually duplicated. As I research this topic, I find that people claim to have a copyright to designs they post on their websites even though some of them are clearly duplicates with the only difference being a slight change – either in the design or the color scheme, or possibly none at all. So, my questions are: (1) Can people claim a copyright to those designs that were clearly derived from other people’s work? What happens if there are designs in my book that fall in this same category? (2) What happens if, in the creative process, you inadvertently duplicate a design someone made of which you are completely unaware? Is there anything that can protect you in this instance? (3) How can anyone truly claim a copyright to art that has been duplicated by so many people for so many years? How do I protect myself? Rangoli artists often share elements -- for example, lotus flowers and leaves, swans and parrots, and certain human imagery. Many times these elements are copied and re-arranged and other times, an artist may create unique elements by hand, without copying. When elements are original, the copyright can be claimed by the artist. When elements are in the public domain -- taken from much older works -- a derivative copyright can be claimed as to the manner in which the elements are re-arranged and as to new elements that are added. But the less modification that is made to public domain elements, the thinner (and less enforceable) the copyright. In other words, the degree of originality matters when seeking to enforce rights over a traditional Rangoli work.

If you copy. If you reproduce someone's original work, or derivative designs over which people claim copyright, then the owner may pursue you in court. That's provided that the owner can register the work, convince a court that it is protectible, and that your use does not constitute fair use. That may be an uphill battle for some Rangoli creators, and not so difficult for some others.

Inadvertent duplication. As for Question #2, if you inadvertently duplicate a Rangoli work -- that is, you create it independently without copying -- then you would not be liable for copyright infringement. As long as you can prove you didn't copy and you created something independently, there is no infringement.

Bottom line. We think there are so many centuries of Rangoli art available, and so you should be able to safely include older public domain Ragnoli works. If you want to reproduce a work and you're unsure of whether it's protected, our suggestion is to keep the image as small as possible as the trend lately has been to permit thumbnail usage of artwork as a fair use. Finally, avoid copying and reproducing large groups of Rangoli from websites. That's because some Rangoli collections may qualify as a compilation copyright which protects the choice and order of the collection but not the individual works.

If you copy. If you reproduce someone's original work, or derivative designs over which people claim copyright, then the owner may pursue you in court. That's provided that the owner can register the work, convince a court that it is protectible, and that your use does not constitute fair use. That may be an uphill battle for some Rangoli creators, and not so difficult for some others.

Inadvertent duplication. As for Question #2, if you inadvertently duplicate a Rangoli work -- that is, you create it independently without copying -- then you would not be liable for copyright infringement. As long as you can prove you didn't copy and you created something independently, there is no infringement.

Bottom line. We think there are so many centuries of Rangoli art available, and so you should be able to safely include older public domain Ragnoli works. If you want to reproduce a work and you're unsure of whether it's protected, our suggestion is to keep the image as small as possible as the trend lately has been to permit thumbnail usage of artwork as a fair use. Finally, avoid copying and reproducing large groups of Rangoli from websites. That's because some Rangoli collections may qualify as a compilation copyright which protects the choice and order of the collection but not the individual works.

Is Dance Troupe Liable for Photo in Background?

|

| N.Y.C. Garbage collector's strike, 1911- horse-drawn cart being stoned (with 'scab' driver hiding inside). |

What do the courts say? There are a handful of cases where unauthorized imagery has appeared as the background in theatrical works, including theater, film, and TV. In one of the better known cases, a court of appeals determined that it was not a fair use to post the poster of a “church quilt” in the background of a television series (for a total of 27 seconds). The court was influenced by the prominence of the poster, its thematic importance for the set decoration of a church, and the fact that it was a conventional practice to license such works for use in television programs. (Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television, Inc., 126 F.3d 70 (2d Cir. 1997).) On the other hand, several copyrighted photographs appeared in the film Seven, prompting the copyright owner of the photographs to sue the producer of the movie. The court held that the photos “appear fleetingly and are obscured, severely out of focus, and virtually unidentifiable.” The court excused the use of the photographs as “de minimis” and didn’t require a fair use analysis. (Sandoval v. New Line Cinema Corp., 147 F.3d 215 (2d Cir. 1998).) Your situation is likely somewhere in between these two cases. We've summarized other fair use cases here (to give you a flavor of how judges rule) and we discuss the four fair use factors, here. We think your case could go either way and will likely be dependent on the duration of the photo's display, whether the display is considered informational and/or for purposes of commentary, and whether the combination of the dance performance and photograph creates a transformative use of the image. This may be one of those cases where an attorney's advice is needed. Assuming you're in Memphis, can you avail yourself of this organization's legal services?

Do I Need Permission to Publish My Animation?

Dear Rich: I have worked in animation for 30 years (as an animator, visual development artist and storyboard artist) and I decided to put together a compilation book of my own artwork (from games, TV shows, and animated Feature films) to sell. It would be self published, probably in a print run of 500 copies, and I would primarily sell it directly at comic book shows and my own website (and perhaps at some specialty shops). I am wrestling with whether to go ahead and print it, without seeking permissions. But, after much deliberation, I began the request process with a few clients that I have recently been working with and so far so good; I have been getting permission with only one firm "NO" so far. But there’s another issue. I used to work at an animation studio that did everything from commercials to TV shows, games, and even effects for feature films. I did TONS of design work for them, on properties they were trying to develop themselves and for clients coming to them for development. The tricky part is that this particular studio has been out of business since 1996 and so I have no way of knowing who actually owns the rights to some of the artwork. So, here are my questions: (1) Do I need to get permissions at all? (2) What is the worst case scenario for not getting permission? (3) Is it legal to just say that I tried to locate the rights holder and could not? And (4) What happens to the intellectual properties of a company that has been out of business for 15 years? Can we answer your questions in reverse order? For some reason we find that more fun. (And speaking of permission, thanks for letting us use one of your images.)

(4) What happens to the intellectual properties of a company that has been out of business for 15 years? The successor to the business owns it. If there is no successor it becomes an orphaned work and a minor annoyance for those who must get permission. For example, if an author has assured her publisher that she will get permissions for her book, she'll have a problem with an orphaned work, and the publisher may make her take the work out. We don't think you need to worry much about that issue, as we explain below.

(3) Is it legal to just say that I tried to locate the rights holder and could not? It's still infringement but it's not a bad idea to put a statement like that on the copyright page and to disclaim copyright in those works. That doesn't mean you may not have to eventually pay for their use but if you can document your attempts to find the owner, that will go a long way to mediating any damages you might be assessed (in the way outside chance you end up in court).

(2) What is the worst case scenario for not getting permission? The worst case is that you run into one of these types and you can't seem to remove their teeth from your pants leg. They will drag you into court and not let go until you get out your checkbook. In your case, this worst case is not a very likely outcome. You have several factors buffeting your position.

First, you have an excellent fair use argument, similar to the argument raised in this case involving the artist Basil Gogos. Gogos created covers for monster movie magazines and the copyright owner of the monster movie magazines sued over the use of the covers in a Gogos biography. A court determined that the use was transformative and permitted it as a fair use. One of the factors in the artist's favor was that the magazines were no longer in print. Another was that the artwork was part of a biography/retrospective of the artist. Another reason that you may not have to worry is the limited publication. It would be difficult for a copyright owner to claim much in the way of damages if only 500 copies were distributed (and money is the main motivator for lawsuits).

1) Do I need to get permissions at all? See above. By the way, did you know it's easy, fast and kind of fun to search copyright office records? We're working on a video to explain the process but until then, check out the Copyright Office search engine.

(4) What happens to the intellectual properties of a company that has been out of business for 15 years? The successor to the business owns it. If there is no successor it becomes an orphaned work and a minor annoyance for those who must get permission. For example, if an author has assured her publisher that she will get permissions for her book, she'll have a problem with an orphaned work, and the publisher may make her take the work out. We don't think you need to worry much about that issue, as we explain below.

(3) Is it legal to just say that I tried to locate the rights holder and could not? It's still infringement but it's not a bad idea to put a statement like that on the copyright page and to disclaim copyright in those works. That doesn't mean you may not have to eventually pay for their use but if you can document your attempts to find the owner, that will go a long way to mediating any damages you might be assessed (in the way outside chance you end up in court).

(2) What is the worst case scenario for not getting permission? The worst case is that you run into one of these types and you can't seem to remove their teeth from your pants leg. They will drag you into court and not let go until you get out your checkbook. In your case, this worst case is not a very likely outcome. You have several factors buffeting your position.

First, you have an excellent fair use argument, similar to the argument raised in this case involving the artist Basil Gogos. Gogos created covers for monster movie magazines and the copyright owner of the monster movie magazines sued over the use of the covers in a Gogos biography. A court determined that the use was transformative and permitted it as a fair use. One of the factors in the artist's favor was that the magazines were no longer in print. Another was that the artwork was part of a biography/retrospective of the artist. Another reason that you may not have to worry is the limited publication. It would be difficult for a copyright owner to claim much in the way of damages if only 500 copies were distributed (and money is the main motivator for lawsuits).

1) Do I need to get permissions at all? See above. By the way, did you know it's easy, fast and kind of fun to search copyright office records? We're working on a video to explain the process but until then, check out the Copyright Office search engine.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)